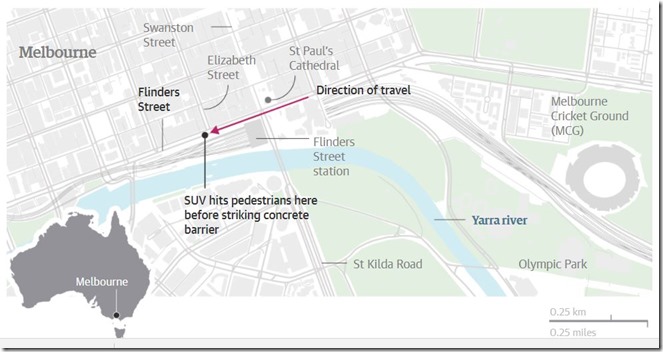

The car ploughed into pedestrians, mostly Christmas shoppers, at a busy junction on Flinders Street in Melbourne, Australia at about 4.30pm local time (5.30am GMT) today. The driver of the white Suzuki Vitara was arrested and taken to hospital, along with 18 people, several of whom are in a critical condition. A second man was arrested who was said to be filming the incident and found to be carrying a bag of knives. The second man was not in the car with the driver and so far is being described as not being connected with the driver. Despite the action of the driver being described as a “deliberate act,” authorities are dismissing the driver as a man with known mental health issues with a history of offender for assault and are saying that the incident is not terror-related.

Melbourne was no doubt on alert for a terror attack, as have cities around the world in the run-up to Christmas. A possible Christmas attack in the UK was thwarted earlier this week. Melbourne itself suffered a similar incident, which was declared to not be a terrorist attack, in January when six people died on Bourke Street in the city after a man drove into pedestrians. In September, a 15-year-old boy was detained after being seen driving erratically down Swanston Street, dressed in black combat gear. Again this was dismissed as not being related to terror. Nevertheless, the city had since these incidents installed concrete blocks around the city, including on Flinders Street, in an attempt to thwart vehicle-based attacks.

Melbourne was no doubt on alert for a terror attack, as have cities around the world in the run-up to Christmas. A possible Christmas attack in the UK was thwarted earlier this week. Melbourne itself suffered a similar incident, which was declared to not be a terrorist attack, in January when six people died on Bourke Street in the city after a man drove into pedestrians. In September, a 15-year-old boy was detained after being seen driving erratically down Swanston Street, dressed in black combat gear. Again this was dismissed as not being related to terror. Nevertheless, the city had since these incidents installed concrete blocks around the city, including on Flinders Street, in an attempt to thwart vehicle-based attacks.

At a press conference in Melbourne the acting police commissioner Shane Patton told reporters that the driver was a 32-year-old man. He was arrested by an off-duty police officer – who sustained shoulder and hand injuries during the arrest. This off-duty police sergeant was on the scene within 15 seconds of it happening and has been taken to hospital where his injuries are said to be non life-threatening. The second man arrested was a 24-year-old man, and it is not known if he had any relationship with the driver or was involved. The obvious thought would be as he was carrying a bag of knives he may have been connected and intent on using the knives. This would be similar to combined vehicle and knife attacks that have occurred elsewhere, including in London this year. Mr Patton, however, seems confident at this point that they are not connected:

“The offender, in this incident, who we are alleging was driving the car, we have reviewed footage and at this stage we are satisfied that he was driving the car without anyone else present at all. He has been taken to hospital as a result of his injuries, as has the police officer. As a result of the attack, a large number of people were injured, some critically.”

The driver is an Australian citizen of Afghan origin. He has a history of drug and mental health issues and was receiving treatment for his mental illness. Mr Patton said that there is no evidence or intelligence at this point that the incident was terror-related: “He is still in custody, under arrest for these offences, for what we allege was a deliberate act. Obviously, at this time, the scene is being worked on by our major collision investigation unit.”

A statement released by Victoria police, Victoria being the southeastern state in which Melbourne is its largest city, said: “Police have saturated the CBD area following an incident where a car has collided with a number of pedestrians on Flinders Street. The incident occurred when the vehicle struck a number of pedestrians in front of Flinders Street station just after 4.30pm. The driver of the vehicle and a second man have been arrested and are in police custody.”

The premier of Victoria in Australia, Daniel Andrews, said that 19 people – including the driver of the car – had been taken to hospital: “Fifteen are in a stable condition. Four are in a critical condition. The offender is one of those patients and is not in a critical condition, and indeed, the off-duty arresting officer […] did suffer some injuries.” Australian prime minster Malcolm Turnbull, tweeted: “As our federal and state police and security agencies work together to secure the scene and investigate this shocking incident our thoughts and prayers are with the victims and the emergency and health workers who are treating them.” The leaser of the Australian opposition, Bill Shorten, tweeted: “Shocking scenes in Melbourne this afternoon. Credit to first responders who are doing us proud once again. Thinking of everyone caught up in this atrocity.”

The scene of the incident is one of the busiest intersections in the city. Police have urged people to avoid the area and local businesses have been told to close. The area is now a crime scene and people who have cars and belongings within the area are being told to leave them there. Police are also calling for public information that may help their investigation: “Police are asking any witnesses to go to the Melbourne West police station at 313 Spencer Street, Melbourne, and all vehicular and pedestrian traffic to avoid the area.”

Whether terror-related or not the incident coming so close to Christmas will create havoc for the businesses and people of Melbourne. Rose Stoupas, the owner of a business, Walker’s Doughnuts, near the scene of the incident told Guardian Australia: “It was mayhem, there were people flying everywhere and the police have ordered all businesses to close their stores. Lots of people were injured, I’m very shocked, the [car] is still there but pedestrians have been cleared mostly from the area … It’s a shitty, shitty day.” Her husband, Jim Stoupas spoke in more detail, speaking to ABC:

“All you could hear was bang, bang, bang, bang. He seemed to be travelling at about 80-100km down Flinders Street in a westerly direction. The intersection was full of pedestrians and he ploughed through pedestrians. The only thing slowing him down was him hitting pedestrians. There was no braking, there was no slowing down. He went straight through the intersection. So whether it was targeted, or whether he’s had a heart attack, or was drunk, I don’t know. He probably hit about 15 to 20 pedestrians. The car stopped because of just, I think, the amount of pedestrians that it had hit. This is the busiest corner in Melbourne. This and Swanston Street corner are the two busiest corners in Melbourne. It was packed. Our store was packed. Pedestrians crossing the road were completely packed. It was solid with people. We were very, very busy in the whole area. All you could hear was the sound of the car hitting people [and] the screams.”

Other eyewitnesses agreed that the driver made no attempt to brake during the incident. One eyewitness, named Sue, who was working at a restaurant nearby told the radio station 3AW: “We could hear this noise. As we looked left, we saw this white car, it just mowed everybody down. People are flying everywhere. We heard thump, thump. People are running everywhere.” The incident only seems to have come to an end when the car crashed into a tramp stop.

David, another eyewitness, this time speaking to ABC Radio, said: “I heard the engine rev and I heard the first thump and I turned around […] I just saw it [the vehicle] ploughing through pedestrians as everyone was crossing the road and then crashing into the tram stop.”

According to one eyewitness, Lachlan Read, the whole incident only lasted about 15 seconds. He told the Herald Sun: “He has gone straight through the red light at pace and it was bang, bang, bang. It was just one after the other.” Meanwhile, Rossella Belardi – who was coming out of Flinders Street station at the time of the incident, told the BBC: “Many people were on the floor and smoke was coming out of the car. Police and the ambulance service were incredible. They came immediately out of nowhere.”

Sources & Further Reading:

- Flinders Street: two arrested after car crashes into pedestrians in Melbourne – The Guardian – Thursday 21 December 2017 – by Melissa Davey, Ben Doherty and Stuart MacFarlane

- Melbourne crash: Driver arrested after hitting pedestrians – BBC – Thursday 21 December 2017

- Melbourne car ramming: no evidence of terror link, say police – as it happened – The Guardian – Thursday 21 December 2017 – by Calla Wahlquist and Christopher Knaus

- ‘Chaos everywhere’: witnesses tell of horror on Flinders Street – The Guardian – Thursday 21 December 2017 – by Melissa Davey and Ben Doherty

- What we know so far about the Flinders Street incident – The Guardian – Thursday 21 December 2017 – by Calla Wahlquist